Santa Barbara County, Sable Offshore Corporation, and Pacific Pipeline Company reached a conditional settlement agreement that allows the two oil companies to proceed with installing 16 safety valves on the Las Flores Pipeline, despite the Board of Supervisors’ inaction nearly a year ago.

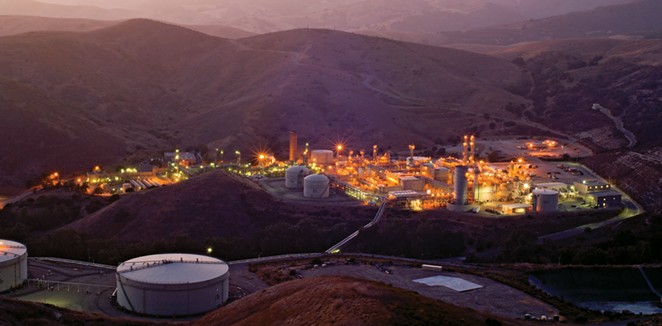

Pacific Pipeline Company—a former subsidiary of ExxonMobil now under the purview of Sable Offshore Corporation after Exxon sold the Santa Ynez Unit and its assets—went through a years-long application and appeals process with Santa Barbara County to install 16 safety valves on the pipeline that ruptured and caused the 2015 Refugio Oil Spill.

It ultimately landed before the Board of Supervisors, which voted 2-2 in August 2023, preventing the county or Pacific Pipeline Company from taking action.

“When that vote took place, it was our jurisdiction, but now Pacific Pipeline Company came to us and said, ‘We are proposing revisions; this pipeline is now going to be underground more than a foot. Because we are doing this, it’s not in your jurisdiction. We don’t need your permission,’” county Public Information Officer Kelsey Gerckens Buttitta told the Sun.

Following supervisors’ inaction, Sable and Pacific Pipeline sued the county for delaying the project and future actions. During litigation, the companies cited a 1988 settlement between the county and Celeron Pipeline Company (a predecessor to Plains All American, which owned the pipeline prior to Sable) that outlines federal and state laws that take away local control when changes (like putting the valves more than a foot underground) occur, she said. Now, it’s in Cal Fire’s Office of the State Fire Marshal’s jurisdiction.

“If we were to keep fighting this in court, it’s not our jurisdiction,” Gerckens Buttitta said. “Pacific Pipeline Company stated it would seek lost revenue, … coming after the county for something that could amount to millions of dollars if we were stalling them.”

Sable Offshore Corporation could not be reached before the Sun’s deadline. Lauren Knight, an ExxonMobil spokesperson, told the Sun that the company can’t comment because it no longer oversees Pacific Pipeline Company.

As part of the settlement, Pacific Pipeline agreed to create a county-based surveillance and response team, trained under the company’s Tactical Response Plan—which will be responsible for initial incident response and early containment. The company will also provide additional training and equipment to county first responders to assist in incident response efforts; install and operate a primary and secondary local operations center; and refurbish the Gaviota pump in its existing station.

“That way, they have local teams, infrastructure, and equipment here at the pipeline. If something happened in the past, they weren’t here to respond,” Gerckens Buttitta said. “While we don’t have jurisdiction, at least in the conditional settlement we have new safety enhancements as well.”

The Environmental Defense Center—on behalf of the Santa Barbara County Action Network and Get Oil Out!—sent a letter to the Planning and Development Department claiming that the county does have jurisdiction over this project and requesting that the county revoke its determination and hold a public hearing on the matter, Chief Counsel Linda Krop told the Sun.

“We didn’t learn about it until it was a done deal. We are pretty upset about the lack of transparency. We are asking the county to slow down, to hold a public hearing, to make it meaningful,” Krop said. “I’ve never seen the county settle without a public hearing because that’s the only way you hear from anyone else.”

Initially, the pipeline was regulated by the federal Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration because it was built as an interstate pipeline, Krop said. During the 2015 spill, federal investigations revealed that oil stayed in the state, reclassifying the line as an intrastate pipeline.

The EDC claims that moving the valves underground is a federal regulation, which doesn’t apply to the pipeline at this time since it’s regulated by the state Office of the Fire Marshal, she said.

“Because lines 901 and 903 were reclassified from interstate to intrastate pipelines, Sable is incorrect that the county’s jurisdiction is preempted here, and thus [Planning and Development’s] acknowledgement was erroneous,” according to the letter from EDC.

In response, the county told the Sun in an email that whether the pipeline is considered interstate or intrastate, the county does not have permit authority or jurisdiction over the safety valves as proposed because they are safety valves required by state law, related to the operation of a pipeline transporting petroleum and/or petroleum products, and 1 foot or more underground.

“Any proposed changes to the pipeline in the future, would be evaluated separately against federal and state law, the Celeron agreement, and the existing permits,” according to the email.